|

|

|

|

|

The legends of Indian press

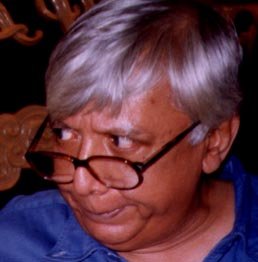

M V. Kamath has been a friend of mine since I was a child. He is now over 80 but had a tremendous part to play in the growth of Indian journalism before it lapsed into its present sordid state. Madhav Kamath was never an elegant writer, but he was an effective one: he could explain abstruse political concepts to the common reader in a language that was always simple and direct, and make him understand what the world he lived in was really like. He has always had a good, inquisitive mind and was an excellent interviewer, partly because he had strong views of his own on most issues. Few young journalists in India today possess any of these qualities, and honestly do not require them, for they are mostly employed to write rubbish.

Cricket writer

I have wondered for years why neither of two eminent members of the Indian press, both my friends, had written their memoirs. K.N. Prabhu was the Chief cricket writer and Sports editor of The Times of India for many years. He knew most of the players and administrators of his time – and even the time before that – fairly well. He not only covered Test series in India but also accompanied the Indian team on several tours. His style was somewhat indebted to that of Sir Neville Cardus, but had unmistakable touches of character and individuality, and he has many cricket stories to tell. Moreover, he tells them well, whether in print or over a drink in some bar. It is a great loss to Indian cricket literature that he never wrote his autobiography. Kamath, after he ceased to work for newspapers, for some years wrote a popular column on politics and current affairs, and also a number of books on a remarkable variety of subjects. But I have always felt that he would be better employed writing about his own life, and now at last he has done so.

The Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan recently released a volume of Kamath's memoirs and all his many friends and admirers will welcome it. For Kamath, in the course of his long life, has achieved success in a large number of things that were all well worth doing, unlike most of the achievers of more recent times. He started as a reporter, as other great Indian journalists of his generation like Behram Contractor did. Like Behram he wound up in the Editor's chair.

They were friends, and worked at The Free Press Journal together soon after the Second World War. A good newspaper reporter has to possess intelligence, almost inexhaustible energy, and a sharp nose for a story. They both had these qualities, which ultimately, and unquestionably, are those that make some journalists stand out from the rank and file.

Before Madhav Kamath joined The Free Press Journal, he had had some interest in a career in medicine, and he was also a nationalist activist. That is to say, he already had some experience of reality, and was well equipped to be a journalist. He worked under S. Sadananand, who became a legendary figure in Indian journalism. But that kind of Indian journalism is now also a legend... almost.

Finally, in the 1950s, PTI sent him to New York as its correspondent. His account of his activities there and his relationship with V.K. Krishna Menon, the Indian ambassador to the United Nations, fascinates me. Khushwant Singh has also written wittily about this strange, saturnine man, who was perhaps the main reason why India and the USA never achieved a friendship that this country badly needed to establish in that era. As Madhav Kamath's career continued, he frequently crossed the path of interesting and historically important figures. His personal life may not have been all that he desired, through no fault of his own. But his professional life and the events and people he was connected with hold the reader's interest throughout.

Afterwards, for some years, he was a correspondent in West Germany and finally in Washington. I met him there in the late '60s or early '70s. When on my arrival from London I called him up, he refused to see me. I was rather surprised, but was later informed that this was because he was annoyed that I had written various articles critical of India. I would have told anyone else to go to hell, but I respected Madhav as a journalist and had fond memories of him as a person. I went to his office next day, presented him with a copy of a new book of mine, and autographed it "To my first real Editor." Madhav recalls this incident in his memoirs, and also the incident that actually made him my first editor. This happened in 1951. I was 13.

Bobby Talyarkhan, another legendary figure in Indian journalism, had encouraged me to write about cricket. My father who knew Madhav, asked him if I could do this for The Free Press Journal. He agreed, but asked my father to send me to see him. He expected someone in his 20s but was instead confronted by a schoolboy in shorts. He thought it was some kind of bad joke, but since he had given his word, sent me to cover a Test match between England and India at the Brabourne Stadium. On the first day my copy surprised him. He thought my father had written it. He demanded that I came to his office directly from the match and wrote next day's report under his scrutiny. This happened on each subsequent day till he was convinced.

So he was my first editor. But this is not the only reason I am fond of him. I have a strong feeling that one should make one's life worth living; make it as rich and full as possible, so that one will not regret a moment of it when one is called on to die. Otherwise it is not worth being born.

M.V. Kamath has lived this kind of life, and has now at last described it in this book. It brings back a period of Indian journalism that no young reporter today even knows of: a period when everyone involved in the press felt responsibility towards the public, the nation, and his or her own conscience.

Gifted person

When Kamath came back to India he edited The Illustrated Weekly of India in one of its last avatars. From then on, in his quiet way, he has continued to work in his own way, on his own books. He has been criticised for his support of a BJP government that has been, if that is possible, worse than any of those that preceded it. But the early part of his book, about his childhood in Goa, where he was friendly with many Christians and regrets not having had more Muslim friends, is touching and explains much.

‘A Reporter At Large’ should be read by anyone interested in what India felt like to a gifted young man in the years immediately before and after the war. It should also be read by anyone who wants to know about the people who have run the country since. Above all, people should read it because it is the autobiography of a man who has done much, not only in his own life but for his country. Young journalists, in particular, should read it. It describes a world and mindset they might otherwise never be aware of.